Longtime readers know that I think and write a lot about arts criticism (specifically in relation to live performance) and criticism as a creative practice unto itself. I fell into cultural criticism by accident, or rather I’ve been writing criticism since the early 90’s when I wrote my first pieces for Seattle’s The Stranger, but I didn’t realize that this type of writing was its own discipline, or the scope and breadth of the ideas and observations one could engage through the form.

Last week, I finally started reading A.O. Scott’s book Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think About Art, Pleasure, Beauty, and Truth and have really been enjoying it. He’s a lively writer who has clearly given the question of criticism a lot of deep consideration, but maintains an accessible voice and style that I appreciate. Over at Culturebot, we always strive to be “deeply informed but widely accessible” out of a belief that even work that is formally experimental and considered “difficult” needn’t be, by providing audiences with a little bit of context and background.

After a thoughtful appraisal of the relationship between artist/object and observer in Marina Abramović’s performance installation “The Artist Is Present” at MoMA, Scott turns his attention to Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo”, asking, among other things, what exactly does it mean when experiencing a work of art demands that “You must change your life” – as indicated in the final line of the poem.

Rilke’s poem vividly describes not the statue itself, this archaic bust of Apollo, possibly in The Louvre, but “what it is like to behold” the statue:

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Like Scott, I have always read this poem as recounting a moment of aesthetic arrest, with the focus of the poem being the description of Rilke’s experience of the work, his interiority as he responds to the sculpture. I had not previously considered in depth what the poem implies about the quality of the sculpture itself, its original context, or the remarkable craftsmanship and artistry required to bring forth so much vivid life from a block of marble.

But this time, in this context, I was struck by what this statue, and Rilke’s response to the statue, tells us about the Classical world. Scott writes, “It is striking that the poem begins by invoking what we don’t see, the head and in particular the eyes, which have presumably crumbled away, lost forever in the middens of time.” [italics mine].

In fact, the statue’s head most likely didn’t crumble away by accident or through the ravages of time and neglect, much more likely is that it was actively and enthusiastically destroyed.

I picked up Better Living Through Criticism after I recently finished reading a very different, and seemingly unrelated, book, The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, by Catherine Nixey.

This well-written and rigorously researched book counters the accepted, mostly benign, narrative around the demise of paganism and rise of Christianity in the waning day of the Roman Empire. Nixey writes:

In a spasm of destruction never seen before—and one that appalled many non-Christians watching it—during the fourth and fifth centuries, the Christian Church demolished, vandalized and melted down a simply staggering quantity of art. Classical statues were knocked from their plinths, defaced, defiled and torn limb from limb. […] Many of the Parthenon sculptures were attacked, faces were mutilated, hands and limbs were hacked off, and gods were decapitated. […] Books—which were often stored in temples—suffered terribly. The remains of the greatest library in the ancient world, a library that had once held perhaps 700,000 volumes, were destroyed in this way by Christians. It was over a millennium before any other library would even come close to its holdings. Works by censured philosophers were forbidden and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.

Nixey describes at great length and in astonishing detail the violent destruction of the Classical world starting, roughly, with Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 CE to 529 CE with the closing of the Academy in Athens by the Emperor Justinian (which some consider the beginning of the Dark Ages) and the introduction of laws in the Justinian Code that “forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labor under the insanity of paganism.”

Almost a decade ago, I read Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, a gripping account of how, in 1417, Poggio Bracciolini, “the greatest book hunter of the Renaissance” discovered the Classical philosopher Lucretius’ poem On the Nature of Things, thought to have been lost for over a millennium.

This discovery, Greenblatt contends, marks a significant turning point in history, reintroducing Classical ideas, long-suppressed under Christianity, such as “that the universe functioned without the aid of gods, that religious fear was damaging to human life, and that matter was made up of very small particles in eternal motion, colliding and swerving in new directions,” thus setting the stage for modernity.

As I recall, Poggio discovered the Lucretius text as a palimpsest. Parchment being scarce, Medieval scribes would often erase Classical texts, especially those deemed particularly heretical, and write ecclesiastical texts on top of them. But sometimes the original texts remained visible beneath the new texts – a palimpsest. And as much as the term palimpsest refers to a specific type of object, it also refers to a way that meaning accretes, and changes, or is obscured, over time, only to be rediscovered later.

Rilke’s poem was published in 1908; his moment of aesthetic arrest is not outside of time, place and context. The poet is encountering, or rediscovering for a new era, the extraordinary vitality, sensuality and artistry of the Classical world at the dawn of Modernism; long after the Renaissance, but still within the penumbra of the Age of Enlightenment (aka The Age of Reason).

Apollo, considered by the Ancients to be the most beautiful god, the ideal of youthful vigor, is the god of archery and oracles, healing and illness, the arts of music, dance and poetry, of knowledge and truth, Light and the Sun.

Rilke’s archaic bust of Apollo stands for everything that was lost when the great Library of Alexandria was destroyed, when thousands of years of philosophy, knowledge and human accomplishment were razed during the violence of the 4th and 5th centuries CE. The sculpture is, in a way, a palimpsest; it holds its original meaning, obscured by centuries of neglect and obfuscation, waiting to be rediscovered by Rilke and the modern age.

And, lest we forget, in 1776, our country’s founders, “brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” – this notion being rooted in the ideals of the Enlightenment:

Based on the metaphor of bringing light to the Dark Age, the Age of the Enlightenment (Siècle des lumières in French and Aufklärung in German) shifted allegiances away from absolute authority, whether religious or political, to more skeptical and optimistic attitudes about human nature, religion and politics. In the American context, thinkers such as Thomas Paine, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin invented and adopted revolutionary ideas about scientific rationality, religious toleration and experimental political organization—ideas that would have far-reaching effects on the development of the fledgling nation.

We are at a fragile, existentially fraught moment in the American Experiment. Many, if not all, of the people currently dismantling the United States government, including the architects of Project 2025, believe that the American Experiment, indeed Liberalism as an ideology, has failed, and are actively working to create an explicitly Christian “postliberal” society.

James M. Patterson, writing in The Dispatch, defines post-liberalism this way:

First, it is an authoritarian ideology adapted from Catholic reactionary movements responding to the French Revolution and, later, World War I. Second, it is a loose international coalition of illiberal, right-wing parties and political actors. Third, it is a set of policy proposals for creating a welfare state for family formation, the government establishment of the Christian religion, and the movement from republican government to administrative despotism.

While not everyone involved in the current post-liberal project shares the same theological foundation, many of them share the same desired outcome: the creation of an explicitly and assertively (white) Christian authoritarian government rooted in pre-Enlightenment theology; the repeal of reason, science and empiricism as governing values; and the imposition of a very narrowly defined punitive, intolerant strand of Christianity that doesn’t resemble the faith currently practiced by many Americans.

Underpinning this intolerance of difference and diversity – of thought, culture and beliefs – is the notion that critical thinking and faith cannot be reconciled; that faith requires absolute submission to one inviolable, unquestionable truth.

And this is the encroaching darkness that occupied my thoughts as I made my way to shul on Saturday. In a stroke of serendipity, last week’s Torah portion was Parshat Bo, which recounts the final three plagues from the ten plagues visited upon the Egyptians during the Exodus story, the ninth of which is … darkness.

In the Jewish tradition, critical inquiry and debate are actually expressions of faith, key components of religious practice. Every word, idea, situation, law, story and perspective in the massive and complex Jewish canon is subject to endless analysis and exegesis. So, in this case, there are many interpretations of what exactly is meant by the plague of “darkness” - what is the nature of this darkness and why was it so horrible?

Maybe the darkness is not merely an absence of light, it is a supernatural, metaphysical darkness, a darkness of the mind, heart and spirit. (h/t to Rabbi Hannah Jensen for her inspiring derashah on the topic!)

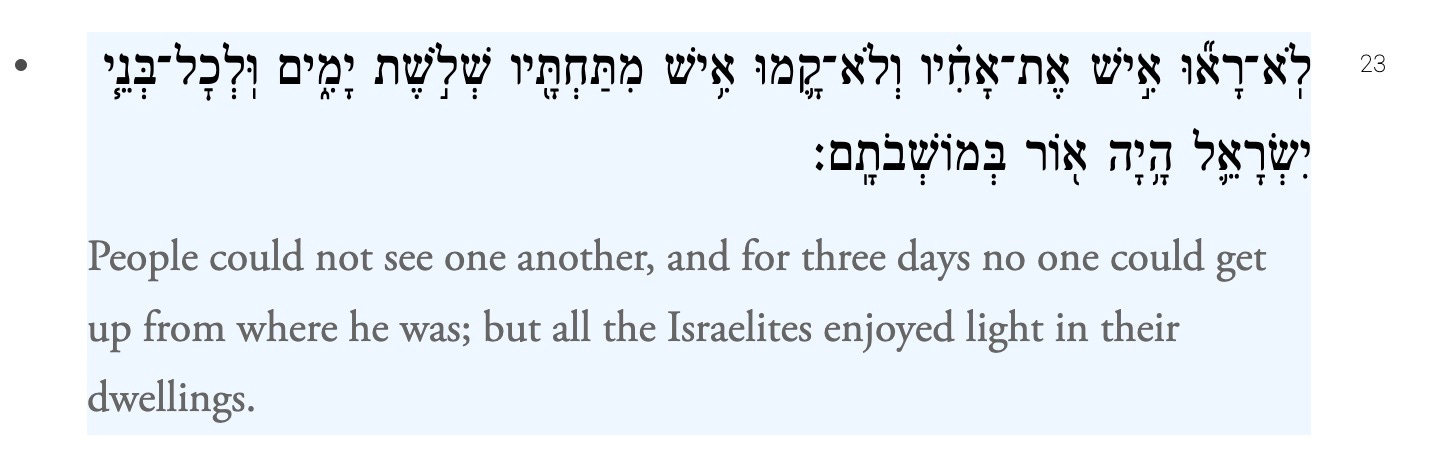

In the original Hebrew text, the first phrase that describes the darkness is translated from the Hebrew in various ways, mostly along the lines of, “People could not see one another.”

But it might also be translated, I think, as “A man could not see his brother,” which I offer here not because of the masculine gendering but because of the closeness specified by the word “brother”.

A man could not see his brother. A man could not see his brother, not fully, not in his wholeness, not as a complex human being. Not even in such a close relationship, where we should know and care for each other, could they truly see and apprehend each other in their fullness.

The Egyptians, the enslavers, cosseted by wealth and privilege, inured from fellow-feeling by solipsism and self-interest, embody a moral blindness that keeps them from seeing their slaves, the Other, as human. To be forced to reckon with their moral blindness and subsequent cruelty, the Egyptians are plagued by an absolute darkness; a terrifying, disorienting abyss of existential despair and impenetrable isolation.

In a sense, we already live in a society plagued by the darkness of isolation. Technology, the unrelenting velocity of modern life, economic precarity, Late Capitalism, geographic dispersal and the rending asunder family ties under these conditions; our commercialized, materialistic worldview which elevates personal expression, fulfillment and achievement over communal obligation and connection – all of these things exacerbate our isolation, keep us in darkness.

Within the social darkness there is individual darkness, and they are interrelated. I have struggled with Major Depressive Disorder for most of my adult life. I know what it is to inhabit the abyss, to feel deeply that there is no way out from under the darkness, no way to end the pain of isolation and despair.

I have learned that much of our understanding of what it means to be an individual is erroneous, we all live in relationship to one another, we are interdependent, we are who we are because of the people around us. Science tells us (!!) it is likely that cognition and consciousness are not individual but co-creative processes, that the construction of reality itself is a consensus project. Thus, when people are isolated and disconnected, when they lose hope and purpose, the darkness descends and rapidly spreads.

The answer to darkness is not more darkness, it is light.

The answer to isolation is not more isolation, but connection.

The answer to fear is not more fear, but courage.

The answer to hatred is not more hatred, but love.

Thank you for reading and spending this time with me. I am grateful for the gift of your attention. I look forward to meeting you out there in the world, where we can teach each other to lead with love, compassion and generosity, and work together to shine a light in the darkness.