Carl Jung, archetypes and Joseph Campbell came up in conversation a few times over the past few weeks. Once when talking about psychedelics and shamanism, another time when talking about using Tarot decks for inspiration when writing and as part of a separate conversation about storytelling. It must be something in the air. Or maybe it’s me. But in any event, archetypal theory has been looming large in my life of late.

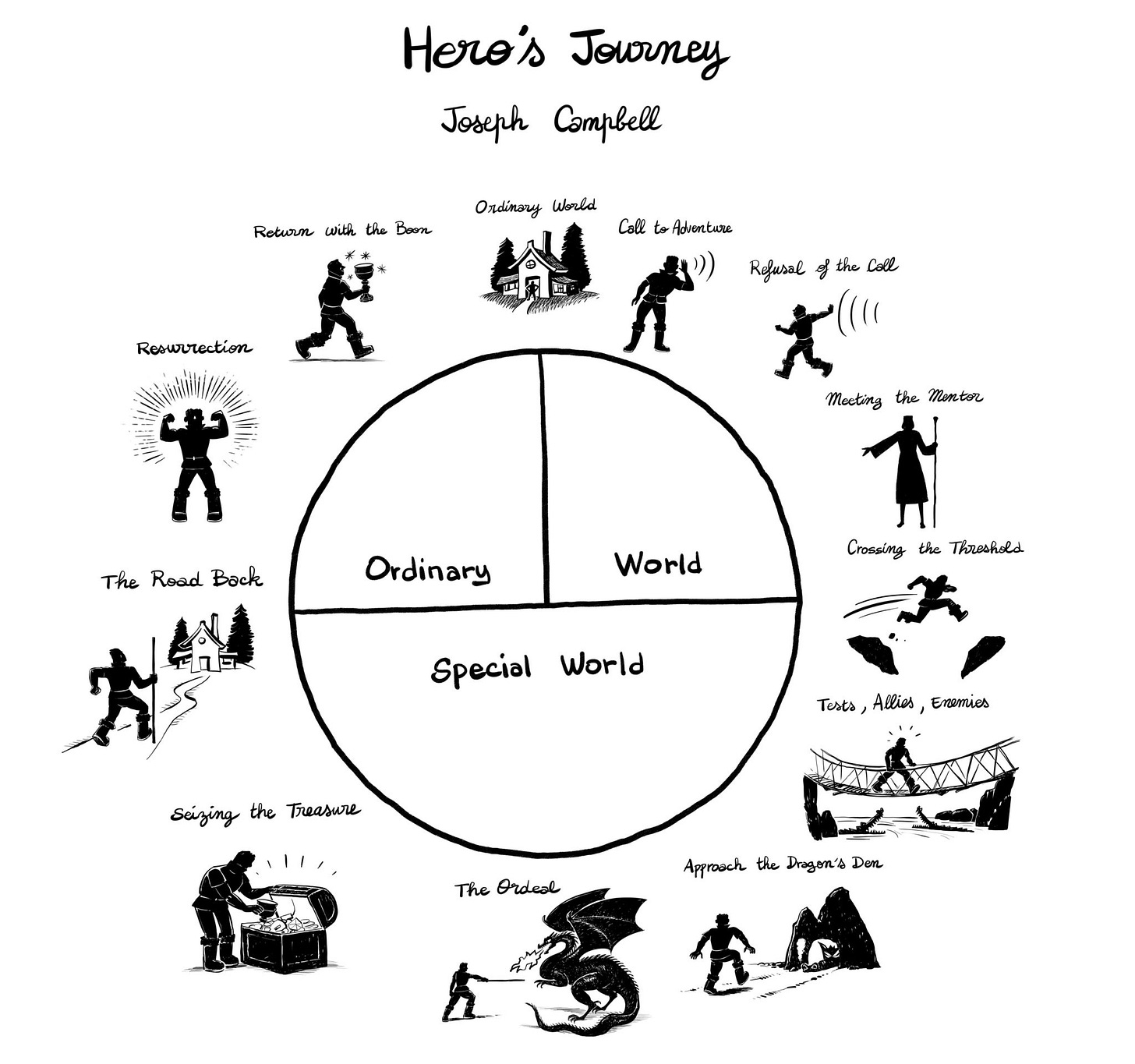

Of course, archetypal theory is never far off in writerly circles. Sit in any Los Angeles café long enough and you’re bound to overhear aspiring screenwriters talking to each other about The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero’s Journey has become widely accepted as the universal structure of narrative storytelling - right up there with the Aristotle’s Six Elements of Drama.- ever since the idea was popularized by Bill Moyers’ six-part PBS series Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth in 1988, and George Lucas cited Campbell’s influence on Star Wars. Unfortunately, the Hero’s Journey is not universal at all, and the presumption that it is universal is, in fact, a function of cultural bias.

I first encountered Jung and Campbell in 1988 or 1989 in a two-part Archetypal Psychology class I took in college. The professor was a remarkable man named Leland Roloff, something of a legend in certain circles, for his sagacious affect and circumspection. He had the habit of listening to students divulge their questions and conflicts and innermost thoughts then silently pausing for a long time, looking into your eyes before pronouncing in his booming bass voice, “Ah! That story.”

I recall having a moment of skepticism around Jung, Campbell and archetypal theory. during that class. I didn’t have the language for it then, but I suspected that because the theory was so deeply situated in Western European philosophy and modes of inquiry that it must, by necessity, be imposing Western cultural biases into its interpretation of other cultures.

Once in class, during a conversation on the Hero’s Journey, I reflected to Professor Roloff that Jewish heroes – specifically in folk stories and Jewish literature – rarely conform to that Epic Heroic structure, that the Jewish hero does the right thing regardless of how that turns out for them personally. Dr. Roloff received the question thoughtfully, I don’t remember how he responded, but there didn’t seem to be space, in the late 1980’s, for critical inquiry into the implicit biases of archetypal psychology.

Why is this relevant now, in 2024?

I started looking at Campbell and the Power of Myth a few weeks ago as I was revisiting the idea of the Perils of Ecstasy that I explored in in the final section of my essay Talkin’ Crunchy Granola Far-Right Lefty Blues. Specifically, I was looking at the role that myth-making plays in the formation of the MAGA Cult, which I suspected was not dissimilar to the myth-making that was foundational to Germany’s Nazi movement.

What I discovered was that, as far back as 1989, Joseph Campbell was known by colleagues to be a racist and antisemite. According to an article in the NY Times, he was an avowed “admirer of figures like Nietzsche, Oswald Spengler and Ezra Pound, all of whom contended that Western civilization was threatened with the rot of decadence,” Campbell thought “the left-wing, liberal, Jewish, Communist point of view was part of the degeneration that was going on in our society. What’s more, Campbell’s oft-quoted mantra of “Follow Your Bliss” is then situated as a kind of spiritual version of “greed is good” individualism that rejects “the notion of fellow feeling or social responsibility.”

It is impossible to say what Campbell would think about the current situation, but if the aforementioned portrait of Campbell is an accurate description of his position on the conditions and causes of Western cultural decadence, then he would feel right at home with Steve Bannon and the other ideological architects of the MAGA movement.

Campbell’s personal beliefs notwithstanding, I bring this up now because it points to the fundamental cultural biases we bring to storytelling, to our understanding of how stories operate, what are the acceptable formats and structures for a story, and what makes a hero a hero?

If we are going to undo and re-imagine unjust, inequitable systems, then we need to interrogate not only those systems, but our fundamental beliefs about how we structure and tell the stories that shape our experience of the world, that power those systems. How do we disrupt our own thinking and storytelling?

I’m thinking specifically of the role of humor, recently, and the way the Harris-Walz campaign has been able to break the relentless doom narrative of the election cycle through irreverence and humor; deflating the MAGA menace through revealing its absurdity.

The menace is no less real, the danger is no less present, than it was before. But we can re-frame the situation, we can redefine the rules of engagement. And in so doing, we have the opportunity to rewrite our larger social and cultural narratives. It is time to muster our imagination and creativity, the forces of joy and humor and affirmation, to keep the darkness at bay and move us ever close to realizing the world as we dream it might be.